Edgar J. Kaufmann House (The Desert House)

Edgar J. Kaufmann House

(The Desert House)

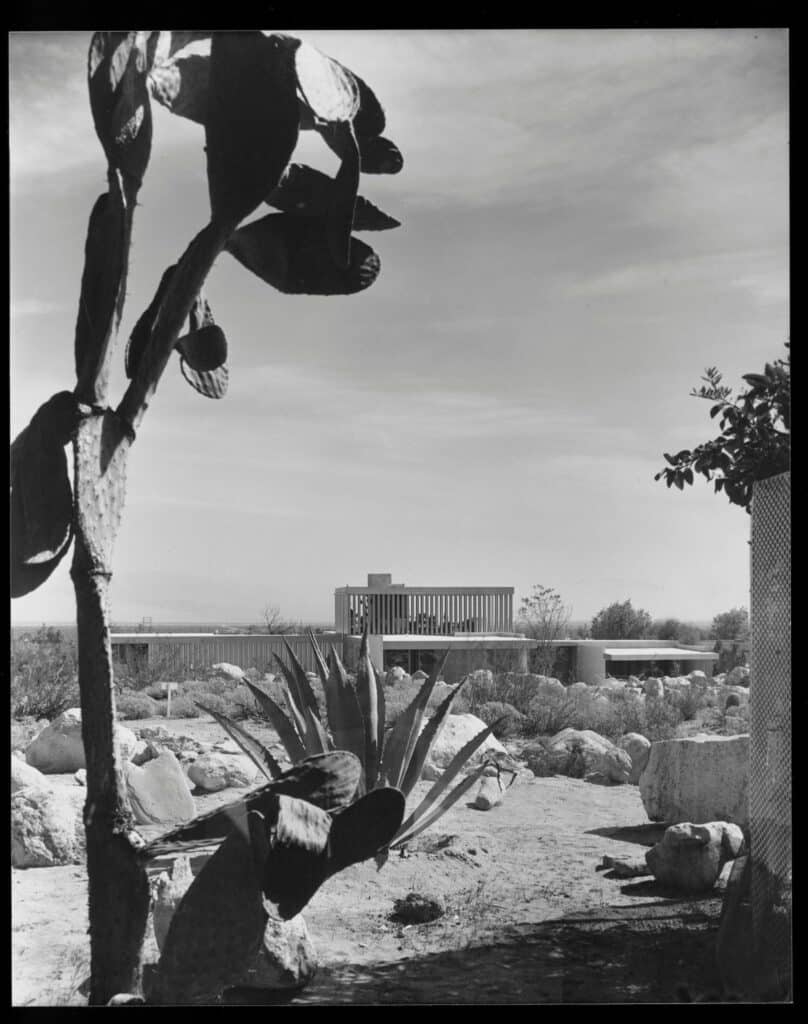

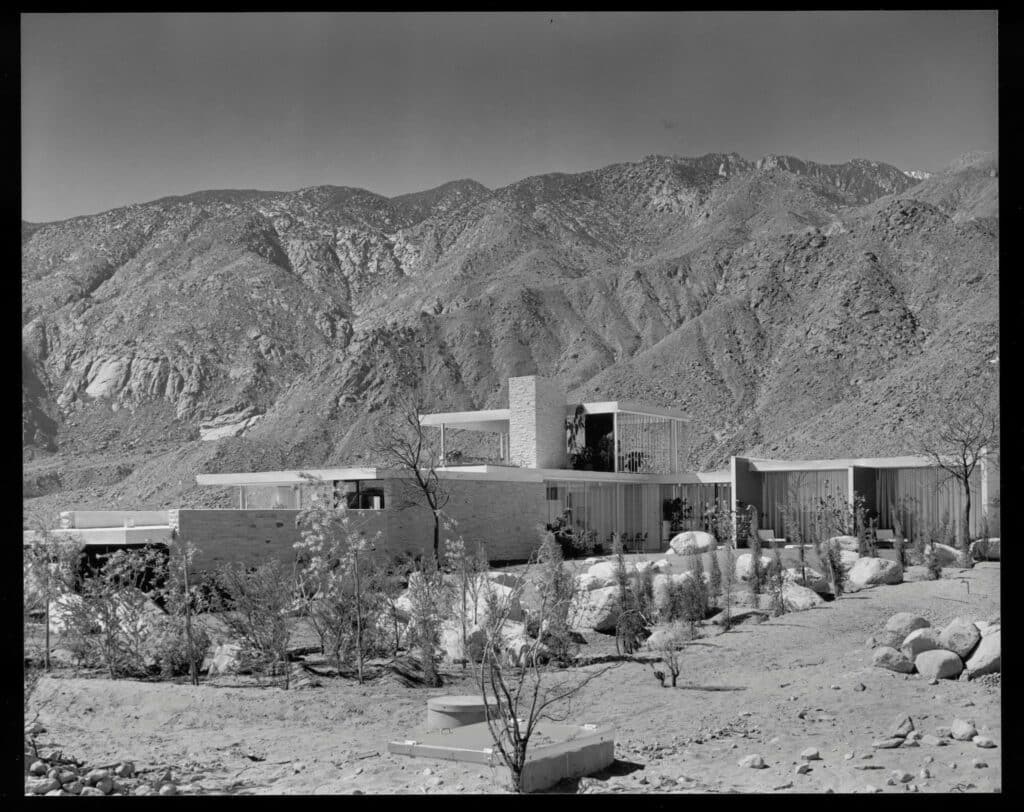

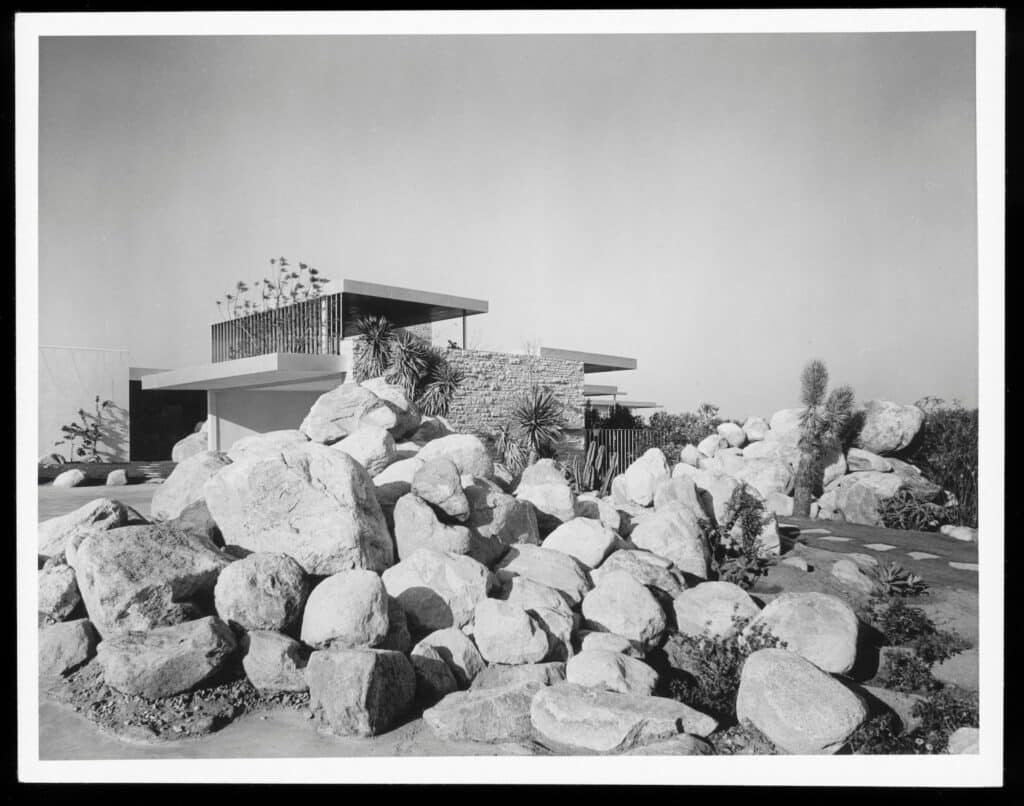

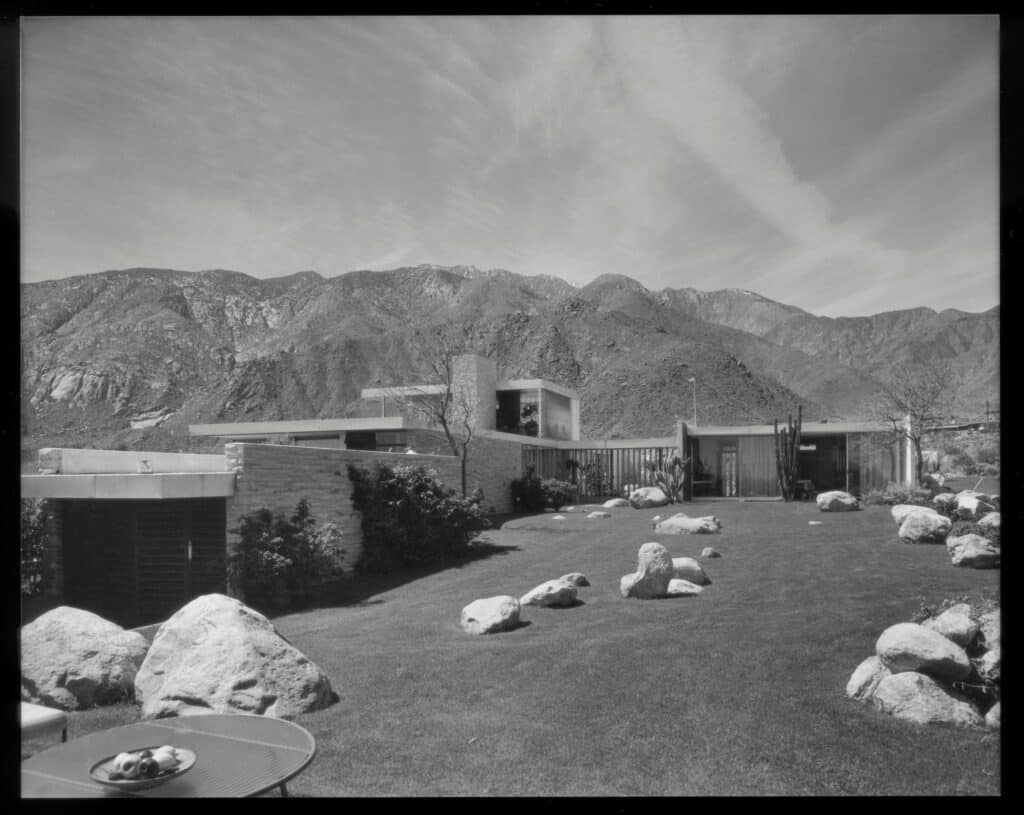

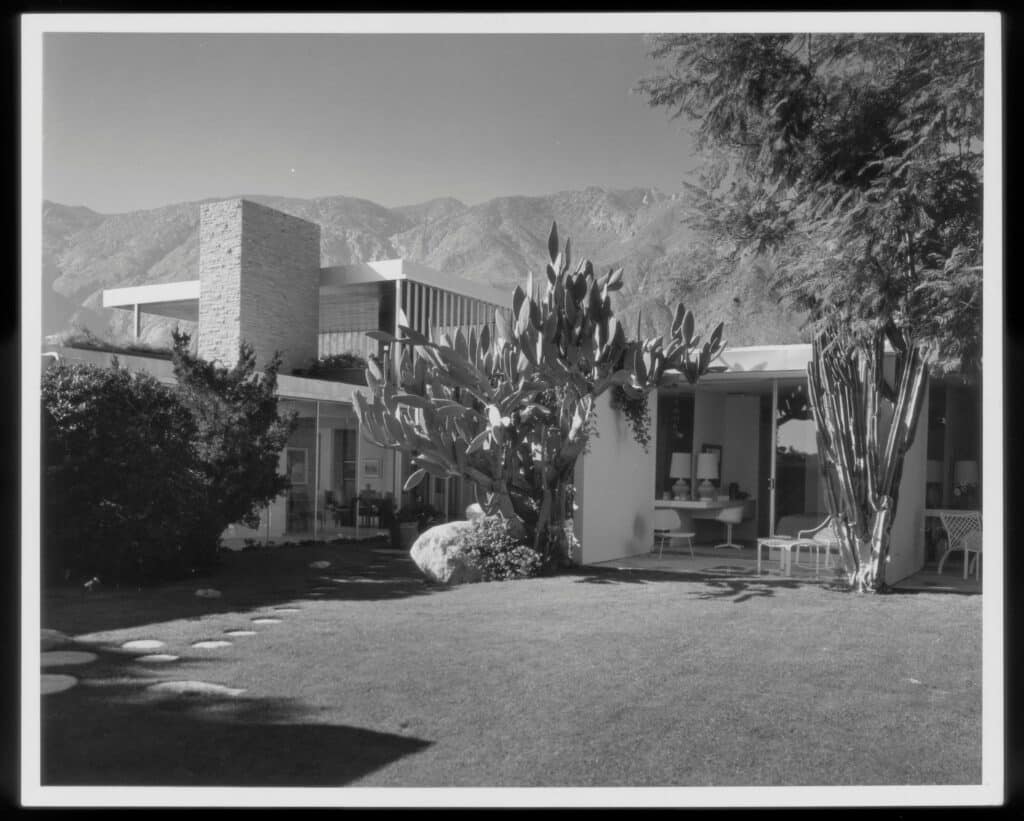

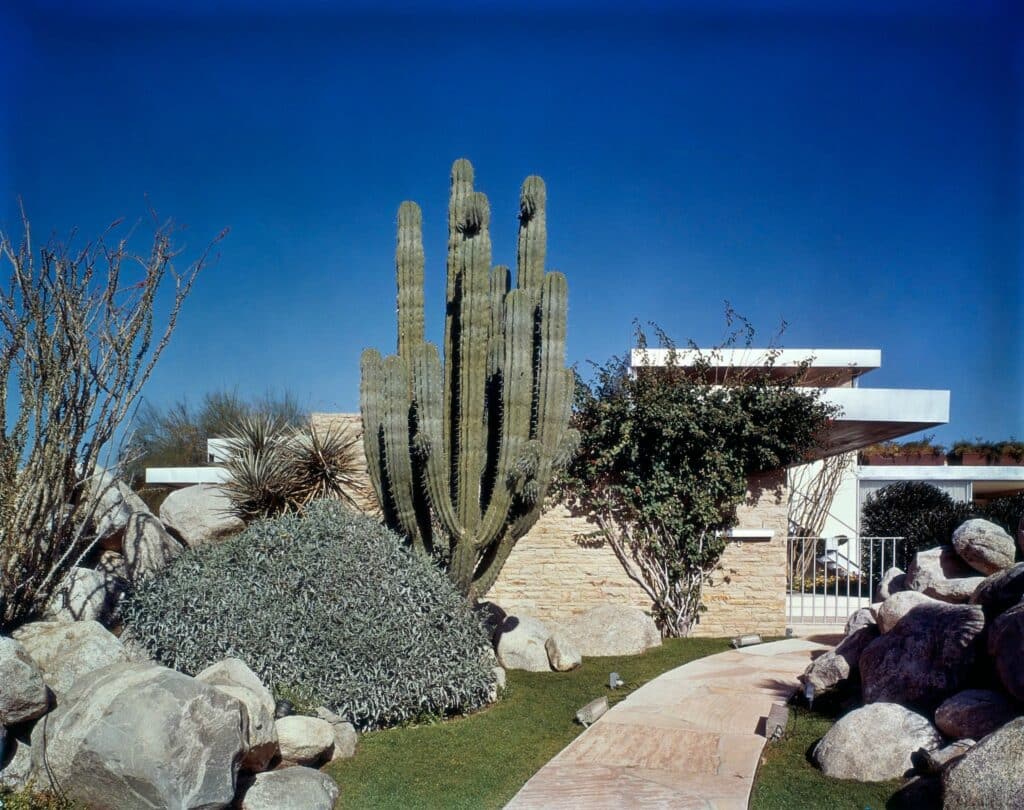

As one of the most well-known houses of the twentieth century, the Edgar Kaufmann House, commonly referred to as the Desert House, exhibits the architectural modernism that its hometown of Palm Springs is celebrated for today. While Palm Springs is frequently associated with the manicured glamor of blue pools and green golf courses, Neutra described the location as the “Badlands of the Cordillera,” suggesting the rocky, barren environs of the San Jacinto Valley (in Neutra’s words, the badlands) and the mountains that rise above it (which he references with the Spanish term, cordillera) were inhospitable to human habitation. Ultimately, these barriers to settlement and development did not deter Neutra or other landmark architects—including William Cody, Craig Ellwood, Albert Frey, John Lautner, Don Wexler, and E. Stewart Williams—from building in Palm Springs.

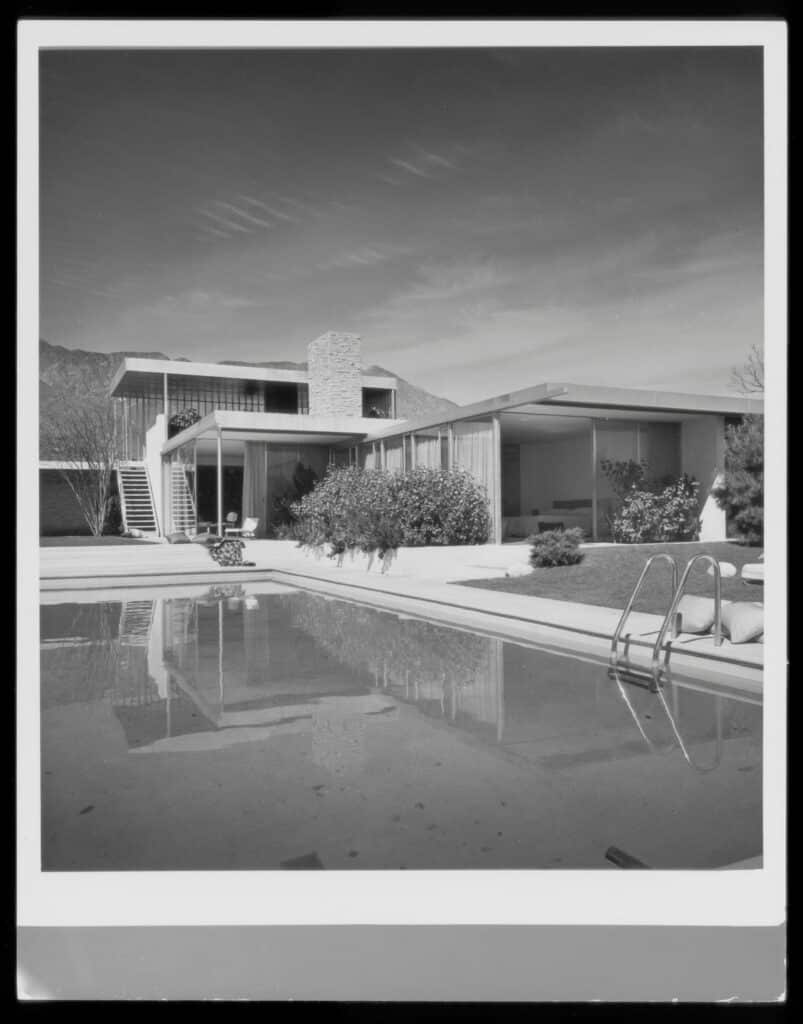

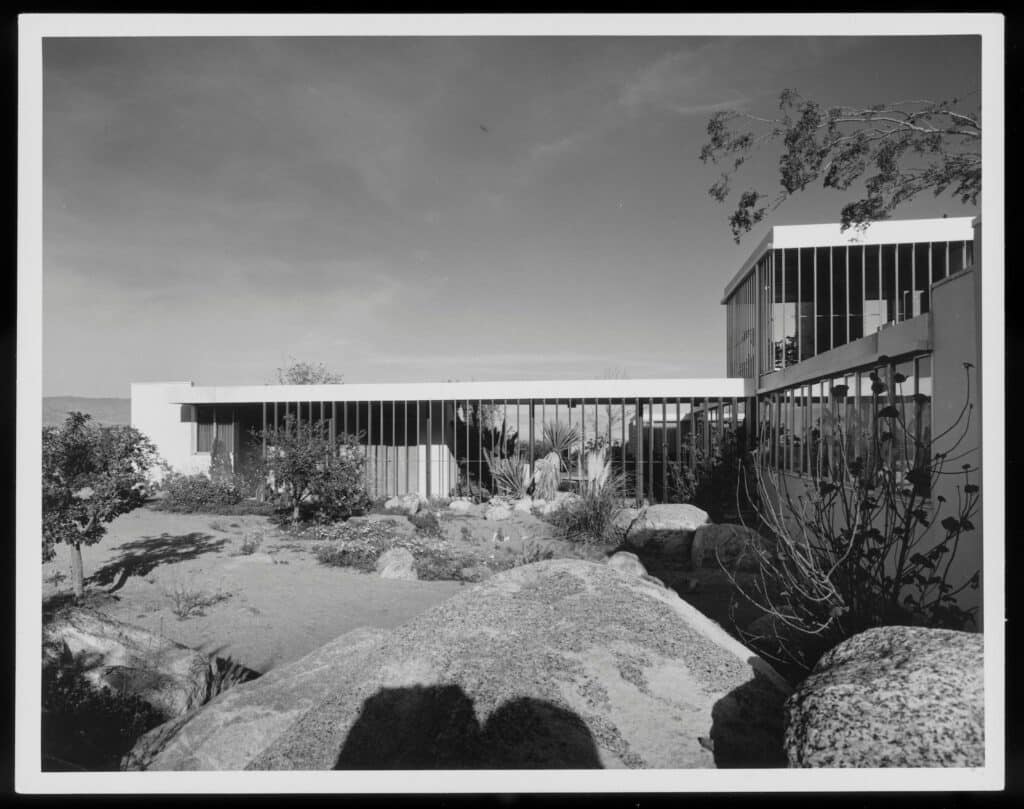

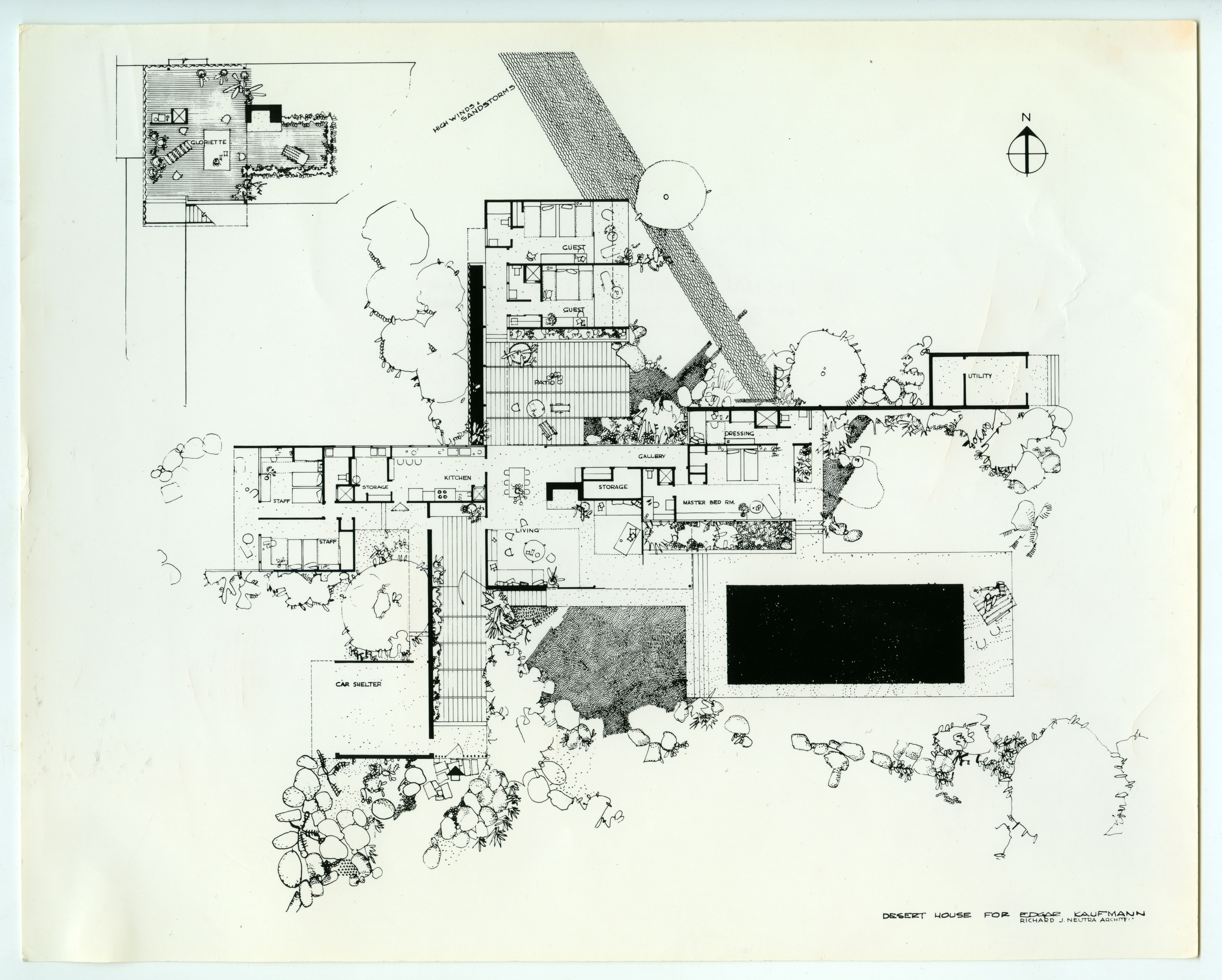

While by 1937, Neutra had completed the Miller House in Palm Springs, and by 1940, Frey had begun his own home in the city, the construction of the Desert House from 1946 to 1947 marked the beginnings of the first of the destination’s grand villas. Neutra referred to the home as “grandiose waste,” and its large footprint in a pinwheel-shaped plan extended out into the desert, announcing its presence. The lavish home was fitting for Neutra’s elite client, the department store magnate Edgar Kaufmann Sr., who came to the project with a sophisticated appreciation for architecture, as evidenced by his earlier commission for Falling Water from the architect Frank Lloyd Wright.

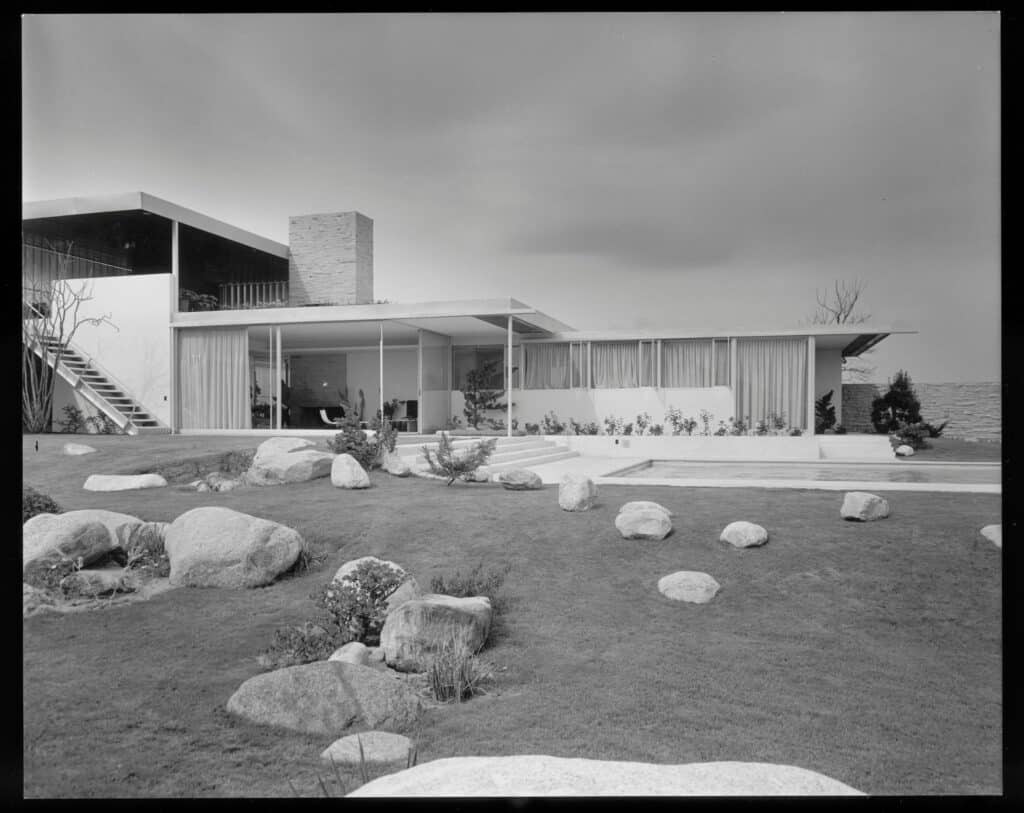

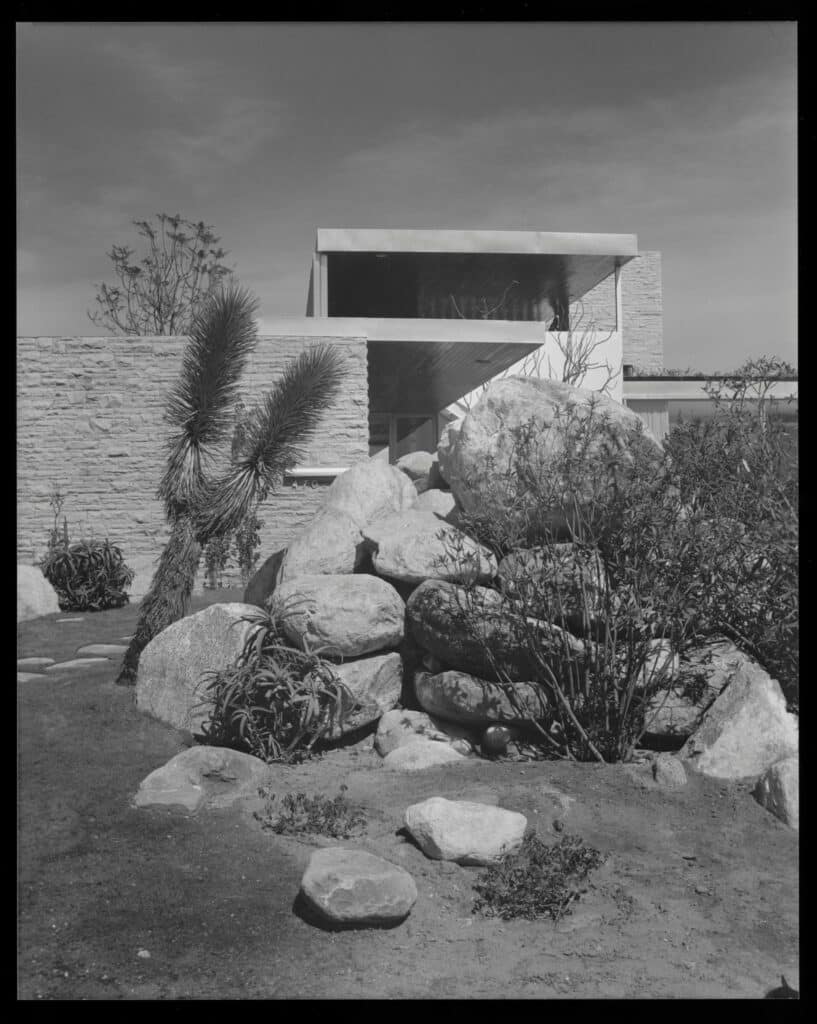

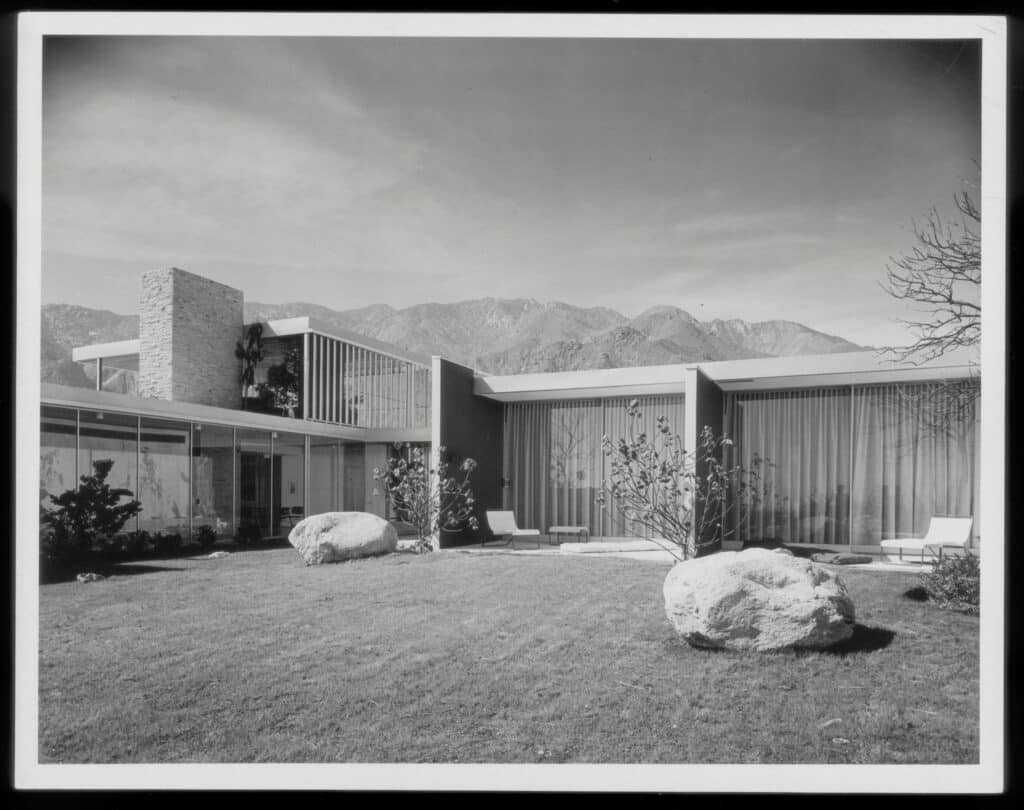

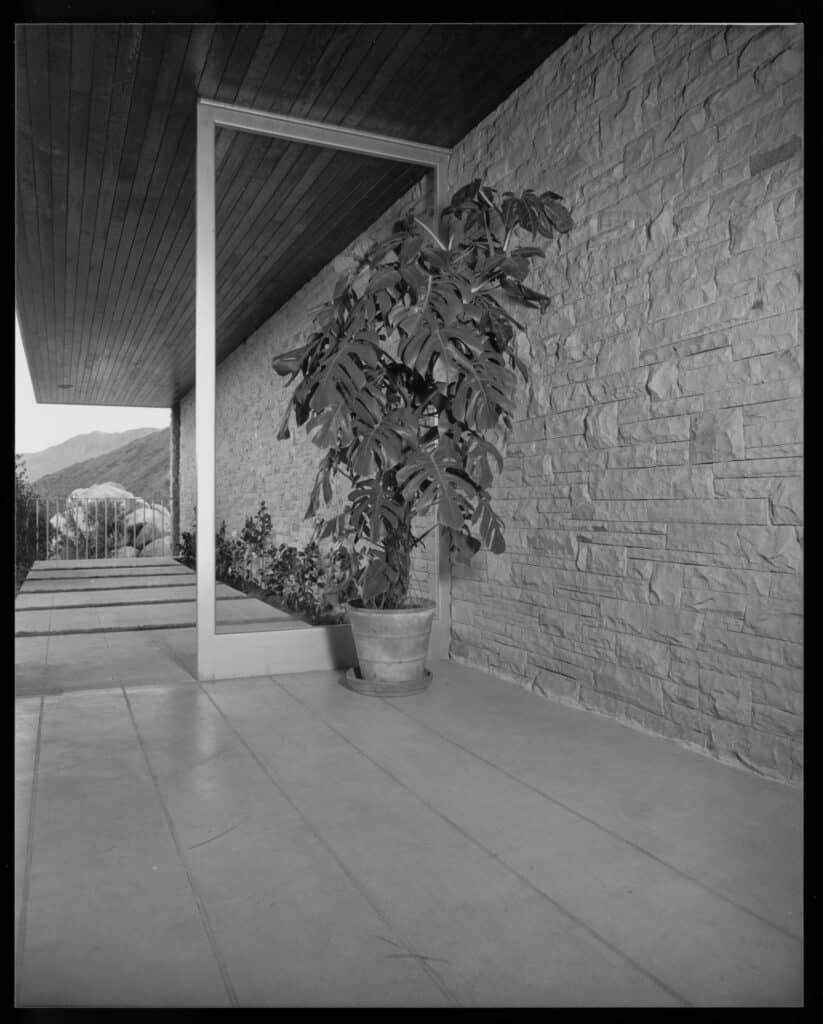

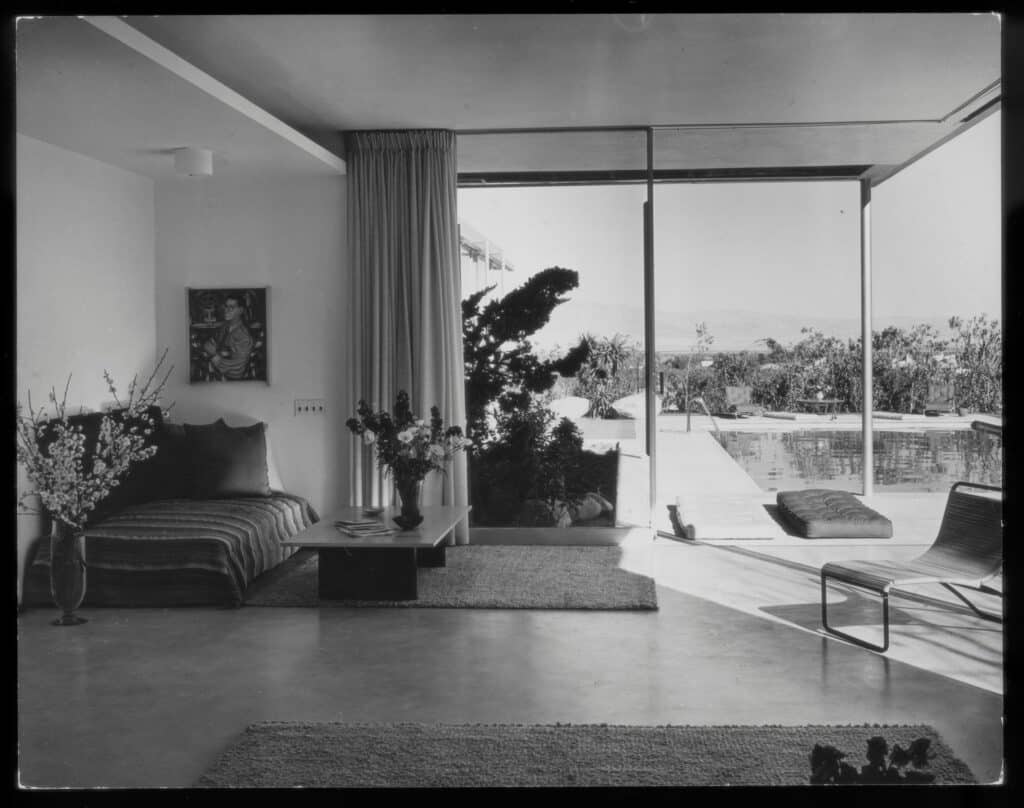

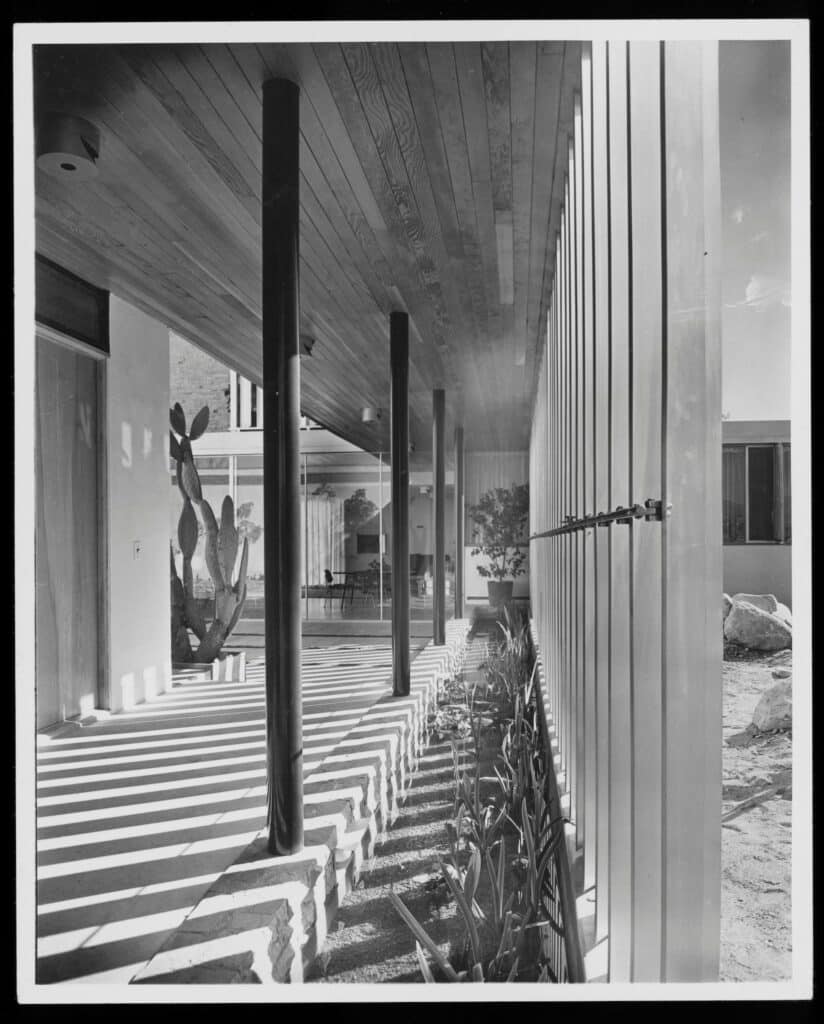

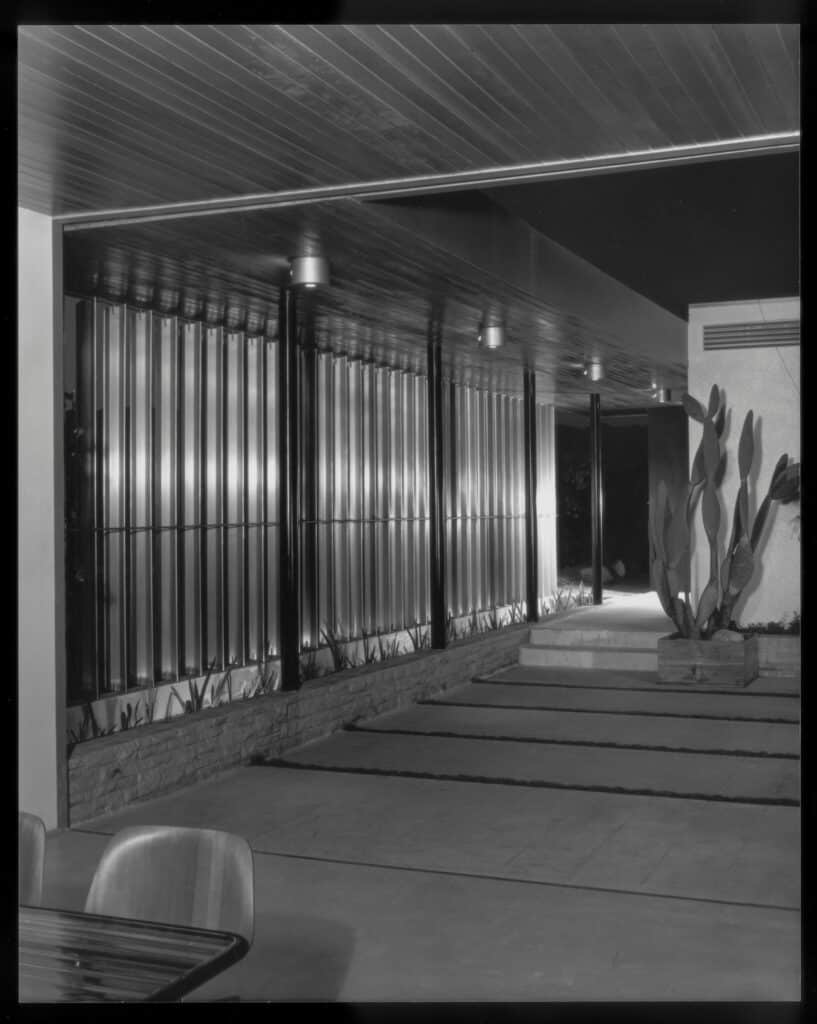

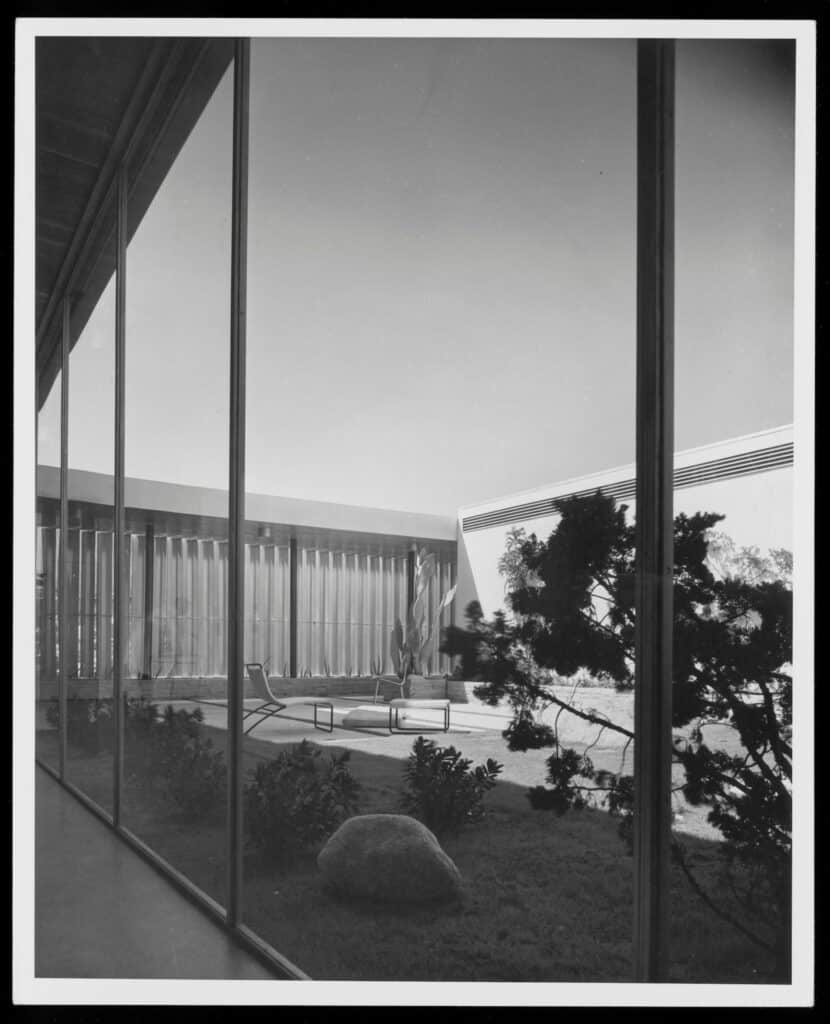

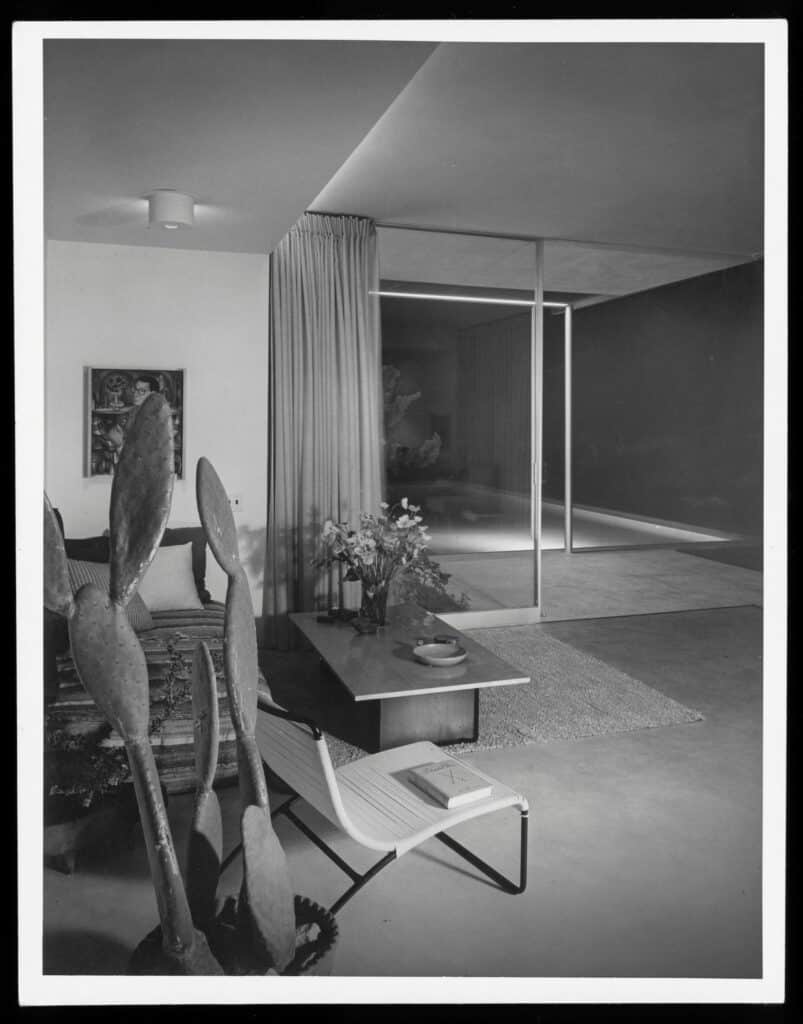

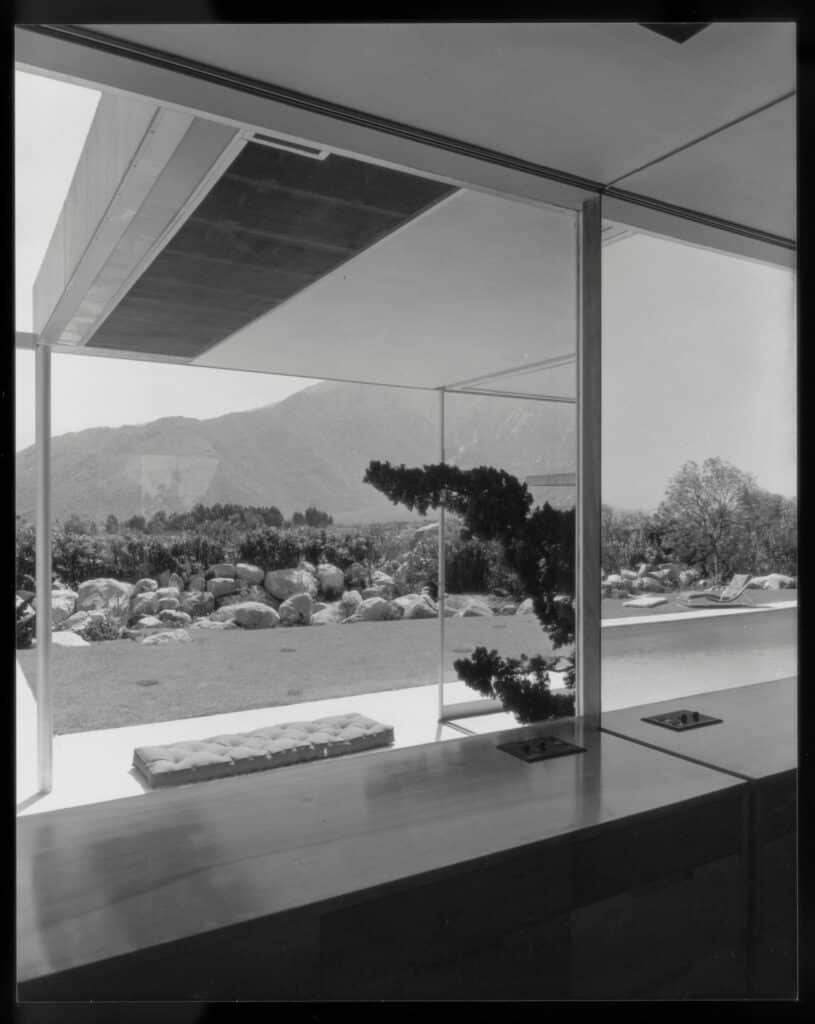

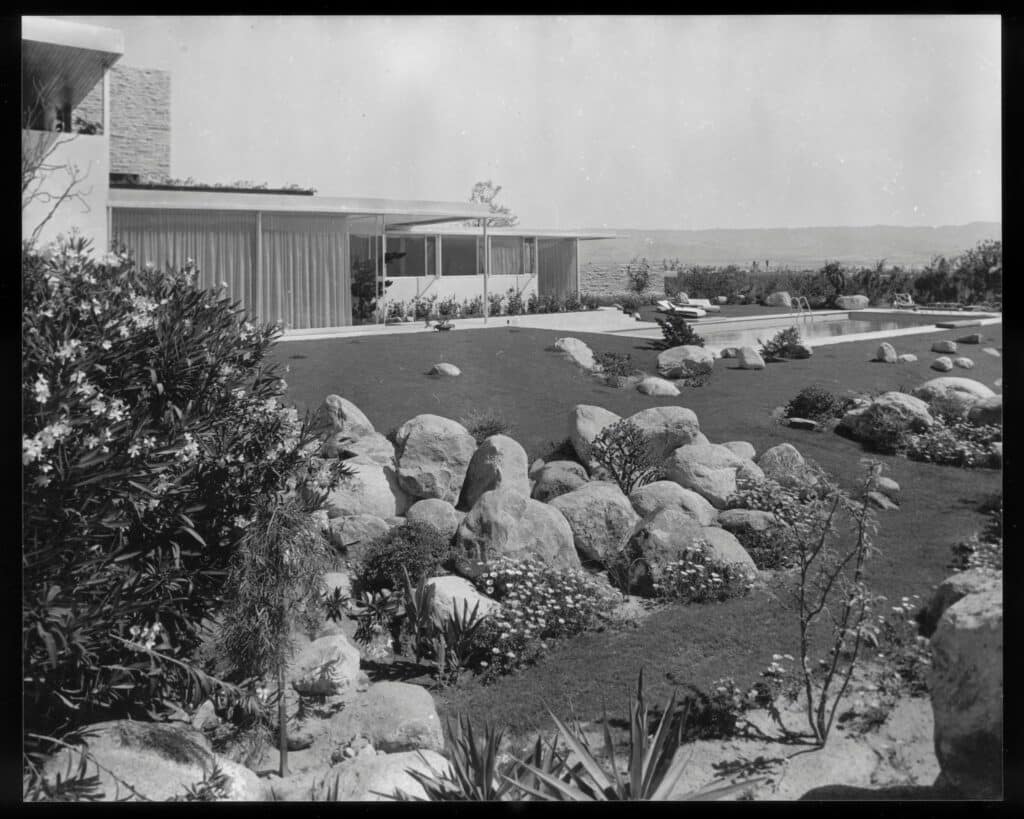

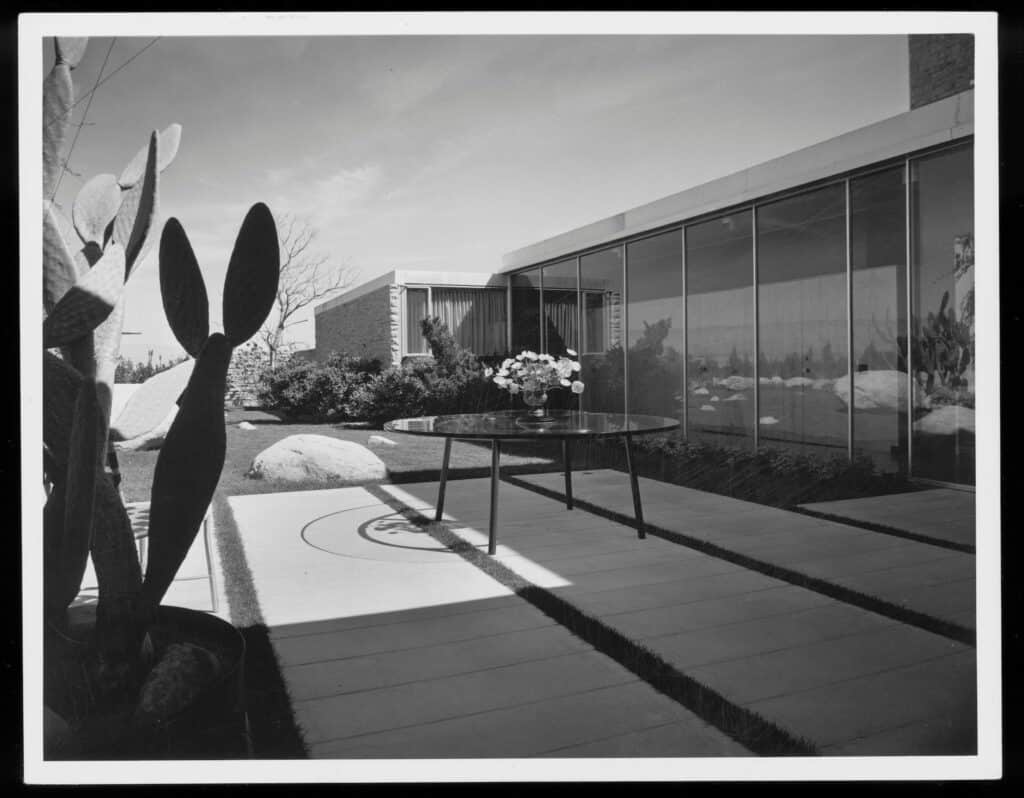

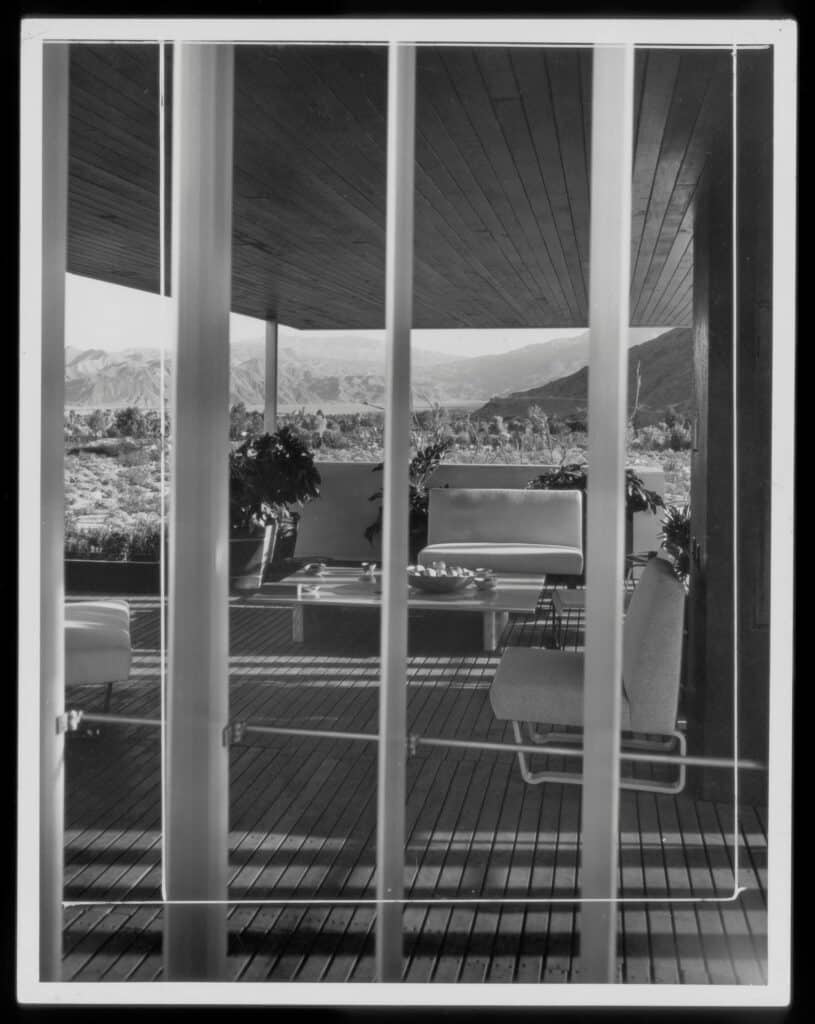

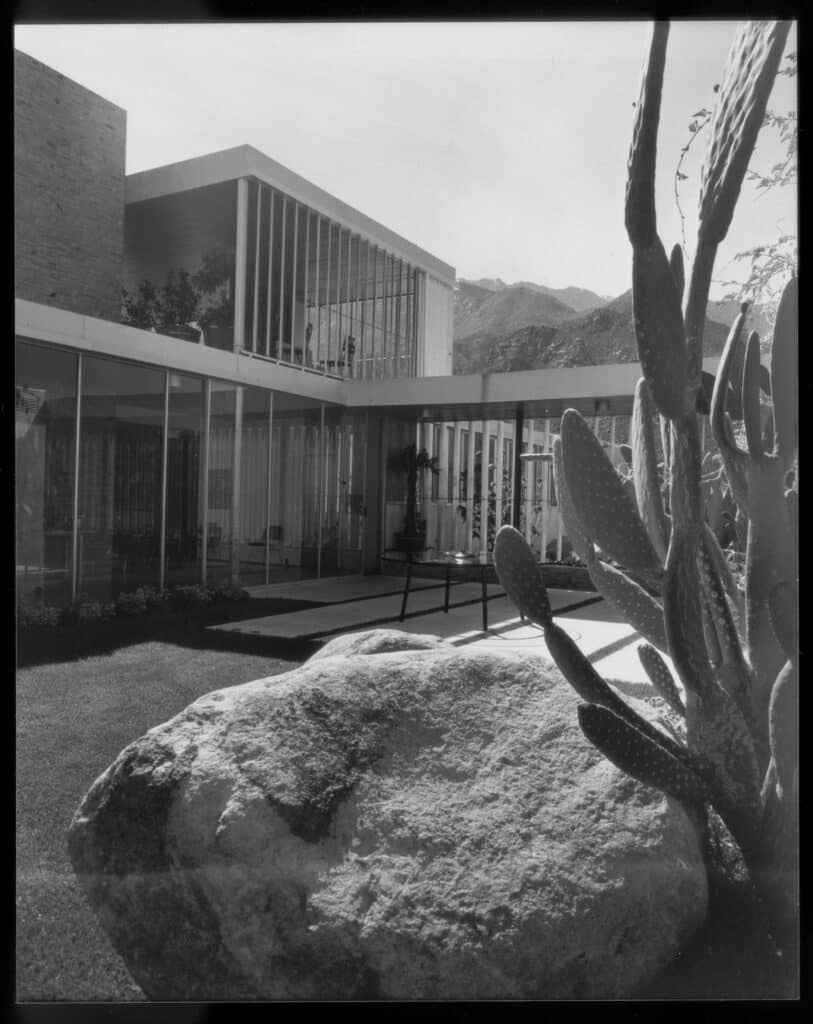

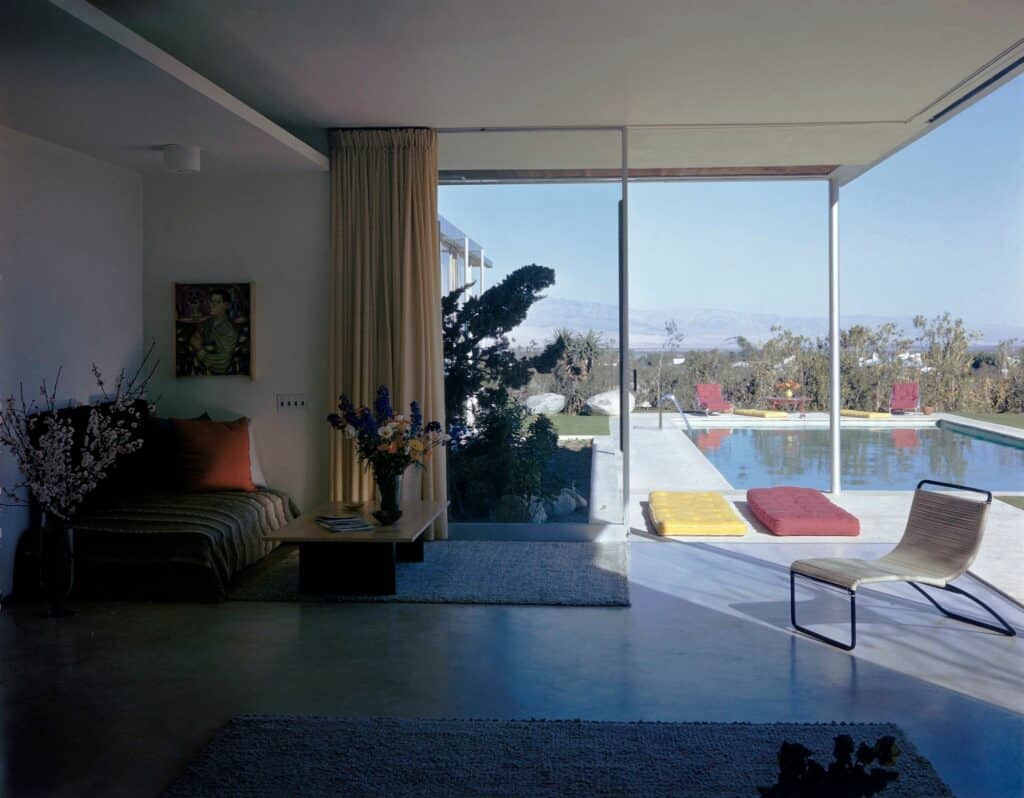

For Kaufmann’s West Coast base, Neutra envisioned a space that would depart from Wright’s approach, and he emphasized these differences in his writing about the Desert House. Instead of integrating easily with the natural environment, Neutra wrote that the building was “inserted” into the harsh backdrop and “set on footings” that would create a juxtaposition between the man-made construction and its surroundings. With a structural system of wood and steel that limited the number of necessary vertical supports to a minimum, Neutra designed a space with walls that seem to slide away, linking the house with the pool area. This is most clear in the southeast corner where the roof of the living room extends beyond the room’s footprint and toward the pool. Similarly, the guest wing was connected to the rest of the house through a protected patio, cooled by a lily pond that spanned the space.

Neutra developed juxtapositions between horizontal and vertical lines, as in his use of vertical aluminum louvers and redwood flooring with a horizontal rhythm. Neutra continued this play with his use of light-colored “Utah buff” stone which runs throughout the house, which, while unifying the space, also is oriented both horizontally and vertically in different areas. The rock’s texture casts shadows that extend this sense of contrast to light and dark. The architect’s intent was evidenced in the carefully planned and executed laying of the stone, achieved by stonemasons Neutra trained himself. Half a century later, in a four-year, multi-million-dollar restoration and reconstruction of the house by Marmol and Radziner for clients Beth and Brent Harris, the same care was dedicated to the stonework, and each stone was individually worked to fill its unique, asymmetric position. The house also features characteristic Neutra details, such as built-in bookshelves with tapered edges.

Adapted from Neutra – Complete Works by Barbara Lamprecht (Taschen, 2000), p. 179.

Project Detail

Year Built

1946–47

Project Architect

Richard Neutra

Client

Edgar J. Kaufmann

Location

Palm Springs, CA